Pre-European Settlement

Before the arrival of European settlers, the area was occupied by hunter-gatherers from three indigenous regional tribes: the Wurundjeri, Boonwurrung and Wathaurong. It was an important meeting place for the Kulin nation alliance clans and critically a source of food and water.

European Settlement 1803-1851

The first European settlement in Victoria was established in 1803, at Sullivan Bay, near Sorrento, but relocated to Hobart, Tasmania in 1804, due to a perceived lack of resources. It was 30 years before settlement was attempted again.

John Batman and Pascoe Fawkner

In 1835, the area which is now central and northern Melbourne was explored by John Batman, a leading member of the Port Phillip Association in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). He negotiated a purchase of 600,000 acres (2,400 km2) with eight Wurundjeri elders. Batman selected a site on the northern bank of the Yarra River, declaring that

“about six miles up, found the river all good water and very deep. This will be the place for a village.”

Batman left eight from New South Wales behind with instructions to build a hut and start a garden, and returned to Launceston to report to the Association.

The same year a different group of settlers, including John Pascoe Fawkner, left Launceston on the ship Enterprise. The party disembarked and established a settlement at the site of the current Melbourne Immigration Museum.

Batman and his group arrived later in the year and the two groups ultimately agreed to share the settlement.

The Governor of New South Wales, Sir Richard Bourke, issued a proclamation in 1835 stating that all treaties with Aborigines for the possession of land would be dealt with as if the Aborigines were trespassers on Crown lands. Later that year, Bourke wrote to the Secretary of State, Baron Glenelg, reporting his action and proposing that a township be marked out and allotments sold.

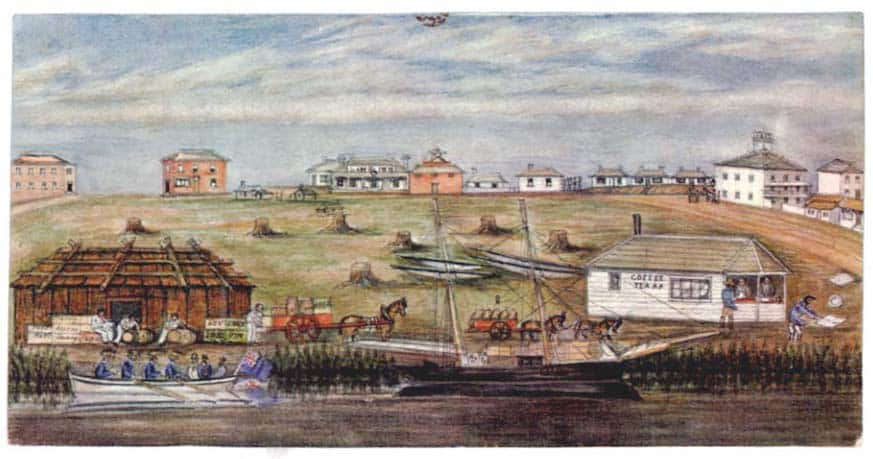

In 1836, Baron Glenelg allowed Bourke to form a settlement. The settlement lacked the essentials of a town (a governing authority, a legal survey and ownership of lands) but the community was law-abiding. Bourke sent a Commissioner to report on affairs. In his report he stated that the settlement, which he called ‘Bearbrass’, comprised 13 buildings: three weatherboard, two slate and eight turf huts. At the time, there was a European population of 177.

Later that year Bourke declared the city the administrative capital of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, and commissioned the first plan for the city, the Hoddle Grid, after the Assistant Surveyor-General Robert Hoddle. The first name suggested by Bourke was Glenelg however later in 1837, the settlement was named “Melbourne” after the British Prime Minister, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne.

It was declared a city in 1847 and in 1851 the Port Phillip District became the separate Colony of Victoria and Melbourne its capital. The city developed around the large natural bay of Port Phillip with its metropolitan hub located at the northernmost point.

By 1860, Melbourne had reached its final form. Most of the land had been sold and many of the sections of the town had attracted special types of occupancies which still characterise the city today. Prior to 1860, a large fountain graced the centre of the intersection of Collins and Swanston Streets, but to enable the laying of tram tracks in these streets in the mid 1860s, it was transferred to the Carlton Gardens, where it still stands today.

Victorian Gold Rush 1851-1891

The discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851 led to the ‘Victorian gold rush’, and the city grew rapidly, serving as the major port and providing the most services for the region. Within months, the city’s population increased by nearly three-quarters, from 25,000 to 40,000 inhabitants and it began to overtake Sydney as the country’s most populous city despite the fact that the Melbourne Morning Herald stated:

“The whole city is gold mad; the city is getting more and more deserted every day”.

The trend to leave the city was only temporary. The gold seekers usually drifted back after a week or two, some successful, some disappointed.

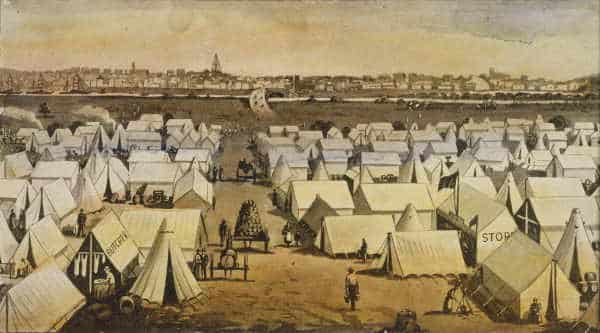

An influx of interstate and overseas migrants, including Irish, German and Chinese, saw the development of slums and a temporary “tent city” established on the southern banks of the Yarra.

Population growth helped stimulate a program of grand civic building commencing with the design and construction of many of the city’s surviving institutional buildings such as the Royal Exhibition building.

The city gained its first public monument and the foundations of St. Paul’s Cathedral were laid. A telephone exchange was established.

Building activity peaked in 1888, with speculative development fuelled by consumer confidence and escalating land value.

As a result of the boom, large commercial buildings, coffee palaces, terraced housing and mansions proliferated in the city. The establishment of a hydraulic facility allowed for the local manufacture of elevators, resulting in the first construction of high-rise buildings. It became home to the world’s tallest office building and the city’s tallest for over half a century. Where previously in the city three or four storey office blocks had been the highest buildings, virtually overnight eight and nine storey buildings were built by private enterprise.

It grew to be the richest city in the world, the largest after London in the British Empire. It hosted two international exhibitions at the Royal Exhibition Building between 1880 and 1890, enabling the construction of several prestigious hotels. This ended in 1891 with a severe depression of the city’s economy.

C20

Pre war period:

The effects of the depression on the city were profound, although it recovered enough to grow slowly during the early C20.

The first federal parliament was convened in the Royal Exhibition Building, subsequently moving to the Victorian Parliament House and later moved to Canberra during this time.

The Council Baths (now City Baths) in Swanston Street were built in 1903. A large number of public buildings were constructed, including Flinders Street Station, City Court and the Melbourne Hospital (now Queen Victoria Hospital).

After World War I, the construction of many public buildings continued, including Spencer Street Bridge in 1929.

Due to the worldwide depression of the 1930s, World War II and postwar building restrictions and material shortages, building development in Melbourne remained fairly static until the early-1950s.

Post-war period

In the immediate years after World War II, the city expanded rapidly.

In 1845, the Council appointed a Public Works Committee, which reported three months later that 400 tree stumps had been grubbed from the main streets of the town but that 1000 still remained to be cleared. By 1849, most of the principal streets were paved, the footpaths gravelled and the centres of the roads metalled. Some streets had kerbed and pitched water channels, while one thoroughfare even had a few oil lamps placed on wooden posts.

Its growth was boosted by post war immigration to Australia, primarily from Southern Europe and the Mediterranean. Whilst the “Paris End” of Collins Street started boutique shopping and open air cafe cultures, the city centre was seen by many as jaded. A polemical situation started to develop.

Suburban Sprawl -v- Highrise development

Car ownership led to suburban sprawl:

In later years, with the rapid rise of vehicle ownership, investment in freeway and highway developments greatly accelerated outward suburban sprawl and declining inner city population. The Bolte government sought to rapidly accelerate the modernisation of the city. Major road projects including the remodelling of St Kilda Junction, the widening of Hoddle Street and the extensive ‘1969 Melbourne Transportation Plan’ changed the face of the city into a car-dominated environment.

This suburban expansion intensified, enhanced by new indoor malls.

The post-war period also saw a major renewal of the CBD which significantly modernised the city.

New fire regulations and redevelopment saw most of the taller pre-war CBD buildings either demolished or partially retained through a policy of facadism. Many larger suburban mansions from the boom era were also either demolished or subdivided. In the lead up to the 1956 Olympic Games the removal of verandahs contributed to the physical change occurring in the CBD.

Height limits in the CBD were lifted in 1958, after the construction of ICI House, transforming the city’s skyline with the introduction of skyscrapers. In the 1960s, the first stage of the Victorian Arts Centre was opened, as was the National Gallery of Victoria.

After a trend of declining population density since World War II, the city has seen increased density in the inner and western suburbs aided in part by Victorian Government planning blueprints, such as Postcode 3000 and Melbourne 2030 which have aimed to curtail the urban sprawl. The government began a series of controversial public housing projects in the inner city by the then Housing Commission of Victoria (now Victorian Office of Housing), which resulted in demolition of many neighbourhoods and a proliferation of high-rise towers.

Building works that altered the city’s skyline and character in the 1980s and 1990s included the redevelopment of the City Baths, State Library, the old Queen Victoria Hospital site and the Queen Victoria Market.

As the centre of the country’s “rust belt”, the city experienced another economic downturn between 1989 to 1992, following the collapse of several local financial institutions. In 1992 the Kennet government started a campaign to revive the economy with an aggressive public works development campaign as well as the promotion of the city as a tourist destination, focussed on major events and sports tourism. The installation of light towers at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in Yarra Park in 1985 and the construction of the National Tennis Centre in Melbourne Park (formerly Flinders Park) represented major alterations to the landscape of one of the city’s principal assets, namely its parks and gardens.

The 1990s saw inner city renewal at Southbank and the creation of the Crown Entertainment Complex and the Melbourne Exhibition and Convention Centre. The Docklands redevelopment began in 1996.

Since the mid-1990s, the city has maintained significant population and employment growth and there has been substantial international investment in the city’s industries and property market.

C21

Major inner-city urban renewal continued in areas such as Port Melbourne, and more recently, South Wharf.

In 2009, the city was less affected by the late-2000s financial crisis in comparison to other Australian cities. At this time the city’s property market remained strong, resulting in historically high property prices and widespread rent increases.

Strategies that have led to enabled this have however included the privatisation of some of the city’s services, including power and public transport, and a reduction in state funding to public services such as health, education and public transport infrastructure.

In 2000, the Melbourne Museum opened in Carlton Gardens, alongside the Royal Exhibition Building and the new public space of Federation Square (locally know as Fed Square) opened in 2002.

Today, the city is the capital and most populous city in Victoria and the most populated in the country. Melbourne is the common name for the urban agglomeration area of the greater metropolis. Its metropolitan area extends south from the City Centre, along the eastern and western shorelines of Port Phillip, and expands into the hinterland. The City Centre is situated in the municipality known as the City of Melbourne, and the metropolitan area consists of a further 30 municipalities. The metropolis has a population of 4.25 million, growing the fastest in numerical terms and 5th fastest in percentage terms since the previous year.

It has also been ranked in the top ten Global University Cities by RMIT‘s Global University Cities Index (since 2006) and the top 20 Global Innovation Cities by the 2thinknow Global Innovation Agency (since 2007).

It is a national cultural centre but perhaps above all accolades, it has been ranked by the The Economist as the world’s most liveable city.

The interest here is to ascertain how and why it has achieved this status.

Author: Mary Bon

Mary is a RIBA accredited architectural researcher, with previous international experience in architectural practice. She has proven research and writing experience for both established clients and innovative start-ups in the construction industry worldwide. She is now based in France and orientated towards bridging the gap between landscape and architecture whilst supporting the causes of local, national and international built and natural heritage.