In December 2010 Russia was selected as the host country for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, for which twelve stadiums must be prepared. At that moment none of the stadiums proposed for the competition were operational. As indicated by the results of PMR’s latest report, entitled “World Cup 2018 in Russia. Planned investments for 2015-2018”, almost four years after the announcement, only three stadiums (in Kazan and Sochi, and Spartak Stadium in Moscow) are operational.

All three venues were built from scratch, have capacities of 40,000-45,000 seats and required more than three years’ work. The stadiums in Kazan and Sochi were built with the use of public funds and needed three years and a few months to be completed, whereas Spartak Stadium, which was built exclusively with the use of private funding, needed four.

It is a huge challenge for Russian officials to develop nine stadiums in less than four years, given that economic progress will fall considerably short of the 2013 predictions. Almost three-and-a-half years before the tournament four projects are still at the preparatory stage. Three stadiums (in Kaliningrad, Rostov-on-Don and Nizhny Novgorod) are to be built from scratch, with another, in Volgograd, to be built on the site of the 12,000-seat Central Stadium. The latter is being dismantled, with the work to be completed in November 2014. This means that contractors will have up to three-and-a-half years to build those four venues, and this will be similar to the amount of time needed to build venues in Sochi and Kazan. However, in accordance with a FIFA requirement, World Cup stadiums must have been in use for over one year at the start of the event. According to PMR, this requirement will be met by six or seven stadiums, with the rest very likely to be activated only a few weeks or months before the first whistle of the tournament.

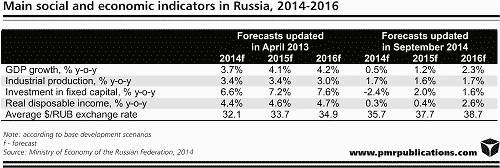

The preparations for the 2018 FIFA World Cup increasingly appear more like a burden than a support for the Russian economy. The macroeconomic conditions in Russia have worsened significantly since the programme was approved in mid-2013. According to the worst-case economic development scenario prepared by the Ministry of Economy in April 2013, the Russian economy was expected to grow by 3.3% on average between 2014 and 2016, whereas the best-case scenario, updated in September 2014, forecasts an average growth rate of 2.4% for this period. However, in November 2014 the Central Bank of Russia predicted that the country’s GDP would increase by only 0.1-0.2% on average between 2014 and 2016.

Note: according to base development scenarios

f-forecast

Source: Ministry of Economy of the Russian Federation, 2014

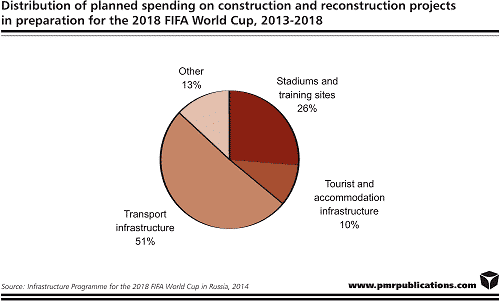

It is likely that there was a strong correlation between the volume and schedule of the funding for the implementation of the Infrastructure Programme for the World Cup and the macroeconomic forecasts prepared by the Ministry of Economy in April 2013. Given that in the near future inflation will be higher and the rouble has been devalued more than the figure predicted in 2013, the total cost of the preparations for the football tournament will considerably exceed the RUB 664bn originally planned. According to the current version of the Infrastructure Programme for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, half of the planned spending on preparations is to be provided from the federal budget, whereas one-third is to come from private investors.

The Russian authorities had planned for more than 95% of the funding needed for the development of the collective accommodation projects to be provided by private investors. At present, most of the host cities are thought not to have enough beds in 1-2-star facilities to accommodate fans, with Moscow and St. Petersburg holding the lion’s share. In addition, there are several cities which lack upmarket hotels. Among the eleven cities which will host 2018 World Cup matches, Saransk, the capital of the Republic of Mordovia, is the weakest in terms of accommodation resources. Hotels and similar facilities located in the Republic of Mordovia, have a combined capacity of less than 1,000 rooms. At present, there are no five-star hotels in the Republic of Mordovia, and only the Meridian (32 rooms) and the recently rebuilt Admiral Hotel (83 rooms) can be categorised as 4-star units. Furthermore, Kaliningrad and Volgograd have fewer than 300 rooms in 4-5-star hotels.

Under the current macroeconomic conditions, private investors are more reluctant to establish new projects in regional cities. Consideration must be given to the manner in which new facilities will be used after the tournament, as the occupancy rates in many host cities are currently far from levels which will encourage the development of new projects. Most of the cities which will host the competition are not popular tourist destinations, and demand for hotel rooms is driven overwhelmingly by business trips. The modest economic growth prospects for Russia for the medium term, the more expensive fund-raising options and Russia’s sharply deteriorating image among developed countries will have an adverse effect on investors’ ambitions for new hospitality projects in Russia.

There is no doubt that Russia will provide all of the required financial resources to complete the hundreds of projects associated with the preparation of the 2018 FIFA World Cup on time. According to PMR, funding from the federal budget will also be provided for many collective accommodation projects currently in the pipeline, despite the fact that no such support is envisaged in the dedicated infrastructure programme. However, support from the federal budget and/or Russia’s sovereign wealth fund most likely will be provided via planned allocations for more strategic infrastructure projects or potential financial support for companies affected by the recently imposed sanctions against Russia.

Tags Industry News News

Constructionshows

Constructionshows