“Preserve and defend culture by turning to our seas to enhance Chilean maritime conscience”

Museo Naval y Maritimo de Valparaiso

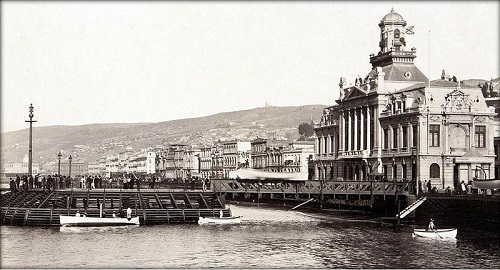

[Image Source] Vintage photograph of Muelle de Pasajeros, Valparaiso

In the 1990s, Architects Myriam Waisberg and later Cecilia Jimenez campaigned to support the heritage of the city. Jiminez carried out a study to ascertain which buildings held heritage value and proposed modifications to the city ‘Plan Regulador Comunal’ in order to protect them. She explained that this was a historical and urban study of the origins of the city, its squares, funiculars, external stairways and landscape which incorporated a value scale showing which buildings should be protected.

The ‘Quinta Jornada de Preservación Arquitectónica y Urbana,’ organised by the Universidad de Valparaíso, took place in 1995 and Jiminez was present. The focus of the debate of this conference was the argument against the development of the city via the construction of high-rise buildings and industrialisation and for the conservation of the city and the development of links between tourism and heritage.

In 1998, grassroots activists eventually convinced the Chilean government and local authorities to apply for UNESCO world heritage status for Valparaíso.

The executive secretary of the Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales drew up a tentative of Sitios de Patrimonio Cultural de Chile (Cultural Heritage sites of Chile) which included Valparaíso.

With the government of Ricardo Lagos Escobar, from 2000, began a new period in which the state supported the heritage cause of Valparaiso. He instructed all his regional ministerial secretaries to involve themselves in this dimension, instigated subsidies for heritage related projects, and consultation with local private organisations such as the Movimiento Ciudadanas por Valparaiso, concerned with the historic city area since the 1990s and the Fundacion Valparaiso, concerned with the port heritage since 1998.

A 23 hectare heritage zone was finally designated with World Heritage status by UNESCO in 2003, as the ‘Historic Quarter of the Seaport City of Valparaíso,’ with a 45 hectare buffer zone flanking it.

The ‘Decima Jornada de Preservación Arquitectónica y Urbana’ took place in 2006.

Today, it can be argued that the conservation policy of the whole city should match the principal objective of the Museo Naval y Maritimo de Valparaiso itself, which as described by the Chilean heritage site nuestro.cl is to

“…Preserve and defend culture by turning to our seas to enhance Chilean maritime conscience…”

Tourism and Cable-Cars

The implications of the development of tourism in Valparaiso have at the outset been related to its hillside development seeking a balance between commercial and civic interests.

The UNESCO designation has led to speculative real estate deals that some allege have led to overdevelopment over the city’s three or four most visited hills with a threat particularly related to the preservation of the city’s funicular cable cars and local communities.

[Image Source] Funicular elevators

Tourist enclaves have displaced permanent residents. The civic network Red Cabildo states that

“…the people who live up in the hills are losing their traditional neighborhoods.

The UNESCO designation is turning Valparaiso into a segregated city…”

and a local association of cable car users states that

“…it’s not just the people who live up the hill who suffer the consequences,

but also the relatives and friends who can’t visit them…”

whilst acknowledging that

“…for visitors, the cable cars provide memories of Chile that they will remember forever…”

In 1996, the World Monuments Fund declared Valparaíso’s unusual system of funicular elevators (highly-inclined cable cars) one of the world’s 100 most endangered historical treasures.

In 1998, the Chilean government declared the cable cars as historic monuments, but little was done to keep them running. The reasons are complex, related to ownership (some stations are privately owned, others are public), administrative turf wars, costs of repairs, alleged unprofitability and, critics contend, incompetence. At the same time, the cable cars are not officially considered public transportation, as they do not conform with safety standards and transport regulations.

In 2004 the Chilean Industrial Heritage Congress event, ‘Elevators and Funiculars of the World,’ highlighted the perceived need for the ‘urgent rescue’ of the ‘world’s most important collection of cable cars and funiculars.’

The Chilean chapter of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) states that

“…the cable car dilemma epitomises the exaggerated importance

given to tourism over everything else in this city…”

The grounded cable cars represent more than disappointed tourists and wounded civic pride. The cable cars that are running now transport through their design, in addition to thousands of visitors, four goddesses (sky, earth, fire and sea) and other allegorical tributes to port myths and legends.

One local suggests that those who use the cable cars daily are not the target of the investment but the tourists and that tourism tends to ‘kill the goose with the golden egg,’ the local heritage.

Tourism and Waterfront Development

[source]

Today, another significant implication for the development of tourism in Valparaiso has appeared, related to balancing commercial container and passenger port and waterfront development whilst addressing the nautical tourism and civic needs for watersports facilities and free access to and from the sea.

Between 1830 and 1831other facilities were built to respond to the advance in commercial and international shipping traffic. In 1832 the first French warehouses were built to hold goods from Europe and Asia.

[source] Commercial Port of Valparaiso

During the 1870s, modernisation works were carried out in the port. Muelle Fiscal was built, the first of its kind in the country. It had an L form and had a main dock crane

able to lift 35 tons and could berth 2 ships. It was in service until around 1919.

Following the opening of Muelle Fiscal, the construction of a passenger ship terminal pier called Muelle Prat started, completed in 1884. It was of timber construction and projected for tens of metres into the sea, becoming a place of leisure for the locals of the time.

The existing small public pier and flanking marina, Muelle Baron was built by an English firm for the state railway service to facilitate the handling of coal between 1912 and 1917, 230m long and 30m wide of timber and concrete construction. It then became an important merchant shipping facility.

In 1980 it became the property of the Empresa Portuaria de Chile and since 1998 the Empresa Portuario de Valparaiso, becoming used for the fruit and horticulture shipping industry.

Since 2002 the Empresa Portuario de Valparaiso with the Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo de Chile transformed it into a pedestrianised public space, retaining two historic dock cranes and often used a public arts space.

In 2004 the Empresa Puerto Olimpico Valparaiso managed a watersports event from the pier and since then it became the country’s first public nautical centre including the Puerto Deportivo building.

Now in 2013, it faces closure in the face of redevelopment for a new commercial centre alongside significant expansion of the port of Valparaiso and local watersports organisations such as Puerto Deportivo Valparaiso are campaigning hard to ensure nautical tourism and watersport facilities are brought about with the new developments envisaged in the Sector Baron and flanking Sector Costanera in line with global counterparts with free public access to and from the sea.

[source] Muelle Baron (Baron Pier)

They are campaigning to ensure that Valparaiso redevelops its public marina as part of a national programme of nautical events and related facilities that bring economic benefit beyond the sport itself. They argue that in the case of Valparaiso and as an integral part of its urban design and insertion in the overall development of the city, the city’s physical orientation, recreational offering and dynamic relationship with the coast needs to be recognised. This will depend upon nautical facilities and event programmes as well as the knowledge of how to create adequate spatial areas, ‘nautical squares,’in the public realm for them, that recognise these considerations and celebrate the history of the city as a seaport, particularly the value of its historic role in the C19 as an exemplary city of world globalisation.

[source] Access from the Sea: Muelle Baron (Baron Pier)

Read also: Part 1 – City Planning

Part 2 – Urban Architectural and Landscape Development

Part 3 – Port and Transport Infrastructure Earthquake and Fire Resistance

Author: Mary Bon

Mary is a RIBA accredited architectural researcher, with previous international experience in architectural practice. She has proven research and writing experience for both established clients and innovative start-ups in the construction industry worldwide. She is now based in France and orientated towards bridging the gap between landscape and architecture whilst supporting the causes of local, national and international built and natural heritage.

Latest Events News

- CONEXPO-CON/AGG Announces the Expansion of Next Level Awards Program and Introduces New Exhibit Design Awards for 2026

- SAMOTER 2026: COUNTDOWN TO THE NEXT INTERNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION MACHINERY EXHIBITION

- Operator Challenge returns to PlantWorx 2025 – JCB joins as headline sponsor

- CIM Leiria Announced as Guest Region at Portugal Smart Cities Summit 2025

- Highly Anticipated Industry Expo Returns to Prince George This Week

Constructionshows

Constructionshows