“…Edinburgh has been the Scottish capital since the C15. It has two distinct areas: the Old Town, dominated by a medieval fortress; and the neoclassical New Town… …The harmonious juxtaposition of these two contrasting historic areas, each with many important buildings, is what gives the city its unique character.” The dramatic topography of the Old Town combined with the planned alignments of key buildings in both the Old and the New Town, results in spectacular views and panoramas and an iconic skyline…” ~UNESCO

Image Source 1581 Plan of Edinburgh (Old Town)

The focus of this article is on the planning history of the Old Town, its dramatic topography and the association it has in part with Sir Patrick Geddes.

Description

[Image Source]: C18 perspective sketch of the Old Town

As described by UNESCO,

“…The Old Town stretches along a high ridge from the Castle on its dramatically situated rock down to the Palace of Holyrood. Its form reflects the burgage plots of the Canongate, founded as an “abbatial burgh” dependent on the Abbey of Holyrood, and the national tradition of building tall on the narrow “tofts” or plots separated by lanes or “closes” which created some of the world’s tallest buildings of their age, the dramatic, robust, and distinctive tenement buildings. (It) is characterized by the survival of the little-altered medieval “fishbone” street pattern of narrow closes, wynds, and courts leading off the spine formed by the High Street, the broadest, longest street in the Old Town, with a sense of enclosed space derived from its width, the height of the buildings lining it, and the small scale of any breaks between them. The renewal and revival of the Old Town in the late C19, and the adaptation of the distinctive Baronial style of building for use in an urban environment, influenced the development of conservation policies for urban environments…”

Pre Medieval and Medieval Development

Further described by UNESCO

“…Edinburgh’s origins as a settlement extend back into prehistory, when its castle rock was fortified, and it may have served as a royal palace in the early historic period. The settlement that grew up was made a royal burgh by King David I (who also founded the nearby Abbey of Holyrood) in around 1125. The separate burgh of canongate, founded c 1140, has long been incorporated within Edinburgh. It was just one of the newly chartered towns of the C12 which set the country’s political and economic development on a new plane, but by the late C15 it was the capital of Scotland.

The Old Town grew along the wide main street (The Royal Mile) stretching from the castle on its rock to the medieval abbey and royal palace of Holyrood. The town was walled from the C15 onwards. lt suffered badly during the English invasion of 1544, and most of the earlier buildings date from the rebuilding after this event. However, the later C16 saw a steady increase in trade; by the early C17 much of the wealth of the nation had come into the hands of the Edinburgh merchant elite, which resulted in considerable new building. The nobility also built town houses, which also contributed to the high quality of the domestic architecture of this period. From as early as the C16 building control was enforced through the Dean of Guild: for example, as a precaution against fire all roofs had to be of tile or slate from 1621, and in 1674 this was extended to building facades, which had henceforth to be in stone.”

The area was dominated by buildings up to 14 stories high.

The Royal Mile

[Photo Credit: Hector Black RIBA RIAS]: Royal Mile street view

The Royal Mile, a name coined in the early C20, is as www.visitscotland.com explains predominantly

“a street of Reformation-era (1560) tenement buildings leading from the seat of Edinburgh Castle on Castle Rock down to the grandiose Palace of Holyroodhouse.”

Narrow closes (alleyways), often no more than a few feet wide, lead downhill on either side of the main spine in a herringbone pattern.

[Photo Credit: Hector Black RIBA RIAS]: Advocates Close

Mary Kings Close

Mary King’s Close was partially demolished and buried under the Royal Exchange and being to the public for many years, became shrouded in myths and urban legends.

However, new research and archaeological evidence has revealed that the close actually consists of a number of closes which were originally narrow streets with tenement houses on either side, stretching up to seven storeys high.

Since 2003 it has become a tourist attraction and also shows the ruins of several others, Pearson’s, Stewart’s and Allen’s Closes.

Gladstone’s Land

Gladstone’s Land contains many C16 and C17 merchants’ and nobles’ houses such as the early C17 restored mansion house of Gladstone’s Land which rises to six storeys.

Edinburgh Castle

[Image Source] ©Adrian Welch – View of Edinburgh Castle

[Photo Credit: Hector Black RIBA RIAS] : South East View of Edinburgh Castle

The Old Town is dominated by a medieval fortress built by King David I in the C12 containing the Chapel of St Margaret, built by King Malcolm III, within the destroyed medieval military fortress on Castle Rock..

Canongate Tolbooth

Canongate Tolbooth, Church of St John is an interesting C16 building, the former seat of justice of the Burgh of Canongate; it is easily identified by its neo-Gothic turreted steeple and clock.

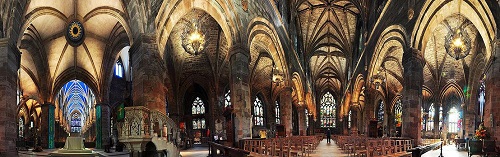

St Gile’s Cathedral

[Photo Credit: Hector Black RIBA RIAS]: View of St Gile’s Cathedral within the Royal Mile

[Image Source] St Giles Cathedral (High Kirk) and vicinity

[Image Source] ©Adrian Welch – View of facade of St Gile’s Cathedral (High Kirk)

[Image Source] Panoramic view of interior of St Gile’s Cathedral (High Kirk)

The C16/C17 St Giles’ Cathedral boasts a vaulted ceiling and ornate tombs

Holyrood House (Holyrood Palace)

[Image Source] 1544 Map of Holyrood Palace at the foot of the Royal Mile

[Image Source] Aerial view of Holyrood Palace Edinburgh

Holyrood House was originally the guest-house of Holyrood Abbey. It was transformed into a royal residence by James IV, and is now the official residence of Elizabeth II in Scotland.

Late C18 and C19 development beyond the Royal Mile:

Old College, University of Edinburgh

In 1789 subscriptions were raised to fund a new university building to a plan prepared by Robert Adam, to replace an existing collection of dilapidated buildings of the University. The foundation stone was laid that year for what was proposed as a building with a First Court giving access to professor’s lodgings, followed by a Great Court, around which the main academic halls and lecture rooms would be arranged.

In 1815 further funds were raised and work recommenced. Plans were submitted by nine architects showing alteration proposals and William Henry Playfair was appointed architect in 1817. Playfair’s design was close to Adam’s but combined the two courts into a single large quadrangle never completed at the time the College was originally constructed.

Image Source Engraving of Old College as seen in 1827

Image Source Old College

Edinburgh Vaults or South Bridge Vaults

The Edinburgh Vaults or South Bridge Vaults, are a series of chambers formed in the nineteen arches of the South Bridge completed in 1788. For around 30 years, during the industrial revolution, the vaults were used to house taverns, cobblers and other tradesmen, and as storage space.

As conditions in the vaults deteriorated, mainly because of damp and poor air quality, businesses left and Edinburgh’s poor moved in, though by around 1820, even they are believed to have left too.

Late C19 development and Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932)

At the end of the C19 during the Reformation there had been a withdrawal from the Old Town as a result of the growth of the New Town. In 1892 Sir Patrick Geddes proposed that it should be regenerated by attracting back to it the university, the bourgeoisie, and the intelligentsia, by converting the High Street (The Royal Mile) into

“…a collegiate street and city comparable in its way with the magnificent High Street of Oxford and its noble surroundings…”

In 1911 Geddes undertook a ‘Civic Survey of Edinburgh.’ He compared Edinburgh with urban-geographical structures in Athens which shows a similar topography. Similar to Athens, he envisaged his ‘cultural acropolis’ to dominate Edinburgh and the region beyond (CIAM 2008). His civic survey prescribed the reuse of older buildings where they still had utility, and many buildings were restored under his direction in the Lawnmarket.

Camera Obscura

[Image Source] View of Camera Obscura at the Castle Hill end of The Royal Mile

Camera Obscura is on the Castlehill section of the Royal Mile. Its origins began on Calton Hill where Maria Theresa Short formed an exhibition observatory some time before 1851. This moved to Castlehill in 1853 and was known as “Short’s Observatory, Museum of Science and Art” from 1853 to 1892. The structure added two storeys to a pre-existing tenement and was turned into small flats in the C18. The main attraction was the camera obscura occupying the topmost room, purchased and refurbished by Geddes in 1892, who transformed it into a “

…place of outlook and a type-museum as a key to a better understanding of Edinburgh and its region…to help people get a clear idea of its relation to the world at large…”

The building then became known as the outlook tower and housed an exhibition of his Civic Survey and is now known as “Camera Obscura & World of Illusions.”

Geddes left Edinburgh (for Montpellier) before his vision could be fully realised although his buildings and philosophy remain. For an appreciation of the latter, read Joyce Earley’s 1953 essay “Sorting in Patrick Geddes’ Outlook Tower.’

Key Ref: Earley J. http://places.designobserver.com/media/pdf/Sorting_in_Pat_720.pdf

Author: Mary Bon

Mary is a RIBA accredited architectural researcher, with previous international experience in architectural practice. She has proven research and writing experience for both established clients and innovative start-ups in the construction industry worldwide. She is now based in France and orientated towards bridging the gap between landscape and architecture whilst supporting the causes of local, national and international built and natural heritage.

This post is part of a series of City heritage and development articles, you can find all of the articles here:

Machu Picchu – The Lost City : Part 1 : City Planning

Machu Picchu: The Lost City – Part 2 : Engineering

Machu Picchu : The ‘Lost City’ – part 3 : Stonework

Machu Picchu: The Lost City – Part 4 : Construction Heritage Significance

Valparaiso : The Seaport City – Part 1: City Planning

Valparaiso : The Seaport City – Part 2:: Urban, architectural and landscape development

Valparaiso ‘The Seaport City’ – Part 3: Port and Transport Infrastructure, Earthquake and Fire Resistance

Valparaiso : The Seaport City – Part 4: Heritage Threats

Marseille : Phocaean City : Part 1 : City History and the Rade

Marseilles: Phocaean City : Part 2 : Heritage within the Urban Framework and Multi-Modal Transport System

Marseille Phocean City: Part 3 : EuroMéditerranée Project

Marseille: Phocaean City: Part 4 : Le Vieux Port

Cape Town : Mother City : Part 1 : Settlement History

Cape Town : The Mother City : Part 2 : Geological Construction Influences and associated Infrastructure

Cape Town: The Mother City: Part 3: Historic Architecture

Cape Town : Mother City : Part 4: Historic Design Figures and Historic Waterfront Renewal

Melbourne: Garden City: Part 1 – Historical Development

Melbourne: Garden City: Part 2 – The Hoddle Grid, C19 and C20 Architectural and Landscape Heritage

Melbourne: Garden City: Part 3 – Public Transport Facilities

Melbourne: Garden City: Part 4 – Urban Sprawl Issues

Edinburgh : Athens of the North : Part I – ‘Old Town’ Planning History

Edinburgh – Athens of the North – Part II: Old Town – Modern and Recent Developments

Edinburgh – Athens of the North – Part III: New Town City Planning History

Edinburgh – Athens of the North – Part IV: New Town – Recent Developments

Constructionshows

Constructionshows