Luke Powers, Founder and CEO, Gearflow.com

MILWAUKEE – The equipment manufacturing industry needs to know that the old rules of our customer engagement have changed.

The world of ecommerce, Amazon, Google, and retail have seemed distant and “next year’s” initiative — until 2020 hit. This year we have seen fear grip the country, dramatic cuts to the economy, and the vertical rocket of tech companies’ share value. Amazon is one the biggest winners with market cap over $ 1 trillion.

Why does that matter for us? Because Amazon has a multitude of business units — all offering the short-term ease of selling on the platform — it is easy to forget the predatory nature of their model. Amazon monitors all the seller and customer data across its channels, giving the company a very unfair advantage when deciding which products to offer themselves.

Basically, sellers give Amazon their customer data so Amazon can decide if they want to compete or not. We don’t need to guess if this is the case — just look at what happened in retail. In order to better understand how Amazon’s business will disrupt our industry, let’s look back to their founding 26 years ago for guidance.

1994: The Genesis of eCommerce

Jeff Bezos embarked on a cross-country road trip from his previous town of employment, New York City, to found Amazon.com in Seattle. Bezos later said he chose Seattle for the concentration of publishers near the city and the engineering talent base of Microsoft. The internet was growing rapidly, and Bezos thought the best entry point to pioneer online commerce was book sales. He noticed that books were among the top of mail-in-catalog sales and reasoned that the internet was a much more efficient way to order.

Amazon launched with over a million book titles — far more than any retail store, including Borders or Barnes & Noble, could stock. Even though the original site was clunky, it gave book enthusiasts far more selection and ease of use than catalogs, book stores, or libraries ever could.

Media attention around Amazon in the early years of the company’s growth focused on the total addressable market of book sales online and Amazon’s mounting losses. The Wall Street Journal even published an infamous article titled “Amazon.bomb” in May 1999 that predicted the imminent demise of the company given competition from book retailers and 1998’s total loss of $125M on $610M revenues. These losses, as we now understand with hindsight, were the wise investments in distribution centers and massive infrastructure to enable Amazon to become the world’s general store. Bezos was not interested in competing 1-on-1 with book retailers, he was looking past them toward a future of dominating online commerce.

However, the world did not see it that way. Traditional bookstores, Borders and Barnes & Noble, were locked in competition for the best real estate for their stores, the best authors to launch their books, and hiring the best retail-operations talent. Bezos, on the other hand, was interested in large and efficient distribution centers outside urban areas and hiring the best software engineers possible. Every penny earned through Amazon’s operations went back into these two areas of investment.

Ever since Amazon’s inception, Bezos has consistently plowed income back into the business to continue aggressive expansion and keep taxes low. Amazon now has over 175 fulfillment centers worldwide with over 150 million square feet. And, according to Glassdoor, Amazon employs over 81,000 software engineers with an average compensation of $136,000.

At Amazon’s IPO in 1997, Wall Street wanted Amazon to focus on short-term profits so they could evaluate the company against traditional retail businesses. Bezos stood firm and never played by the same rules. In his famous 1997 original letter to investors, he stated:

“We believe that a fundamental measure of our success will be the shareholder value we create over the long term. This value will be a direct result of our ability to extend and solidify our current market leadership position. The stronger our market leadership, the more powerful our economic model…”

In 1997, Bezos had the foresight that his philosophy would pay massive dividends in the long run, given the annual compounding growth of ecommerce sales. He could anticipate the changing habits of consumers and was dead-set on Amazon being in the best position to become the winner-take-all ecommerce retailer.

While the worlds of booksellers, record stores, and shoe retailers were locked in fierce competition and quarterly profits, Amazon went about their business creating a future by their own rules. Does this sound familiar to today’s construction equipment and parts industry?

In order to understand what rules Amazon plays by, let’s dive into their famous “Virtuous Cycle” flywheel.

The (Un)Virtuous Amazon Cycle for Sellers

According to Jeff Wilke, CEO of Worldwide Consumer at Amazon, Jeff Bezos drew a sketch on a napkin about the self-reinforcing momentum of Amazon’s business. He donned it the “Virtuous Cycle.”

This flywheel will no doubt be studied in MBA classes for at least a generation. However, notice the word “virtuous” in Bezos’ title. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, “virtue” is defined as “a particular moral excellence” or “a commendable quality or trait.” As you can see, this cycle is self-reinforcing for Amazon — not their sellers. It is certainly a commendable monopolistic quality for Amazon, but not of a particular moral excellence.

As we know, Amazon’s huge bets in distribution centers and the best engineering talent have made them the de facto place to sell online. However, even though the platform is incredibly easy to use, have sellers considered the true long-term cost to their businesses?

In the short term, sellers are happy to be a part of Amazon’s “virtuous” cycle, because they believe it can only produce an upside for them. Amazon did the hard work of engineering a great platform and the cost of running mega and efficient distribution centers — what’s not to like? In fact, they double down on selling on Amazon by purchasing Sponsored Products ads and sending their products to Amazon’s fulfillment centers for Prime shipping (both significantly increasing the cost of doing business on the platform). The Sponsored Products advertising revenue was nearly $5 billion in Q4 2019.

As more and more sellers join and compete on the platform, Amazon gathers more and more data on their products. This rich data set includes:

- Impressions

- Clicks,

- Search queries

- Q&As

- Reviews

- Returns

- Revenue trends

MBAs working at Amazon then take this data and strategize on which product segments would be a good fit for Amazon to take advantage of in the future.

As we know this is not the only rich set of data Amazon has at their disposal to determine which products to sell themselves. Amazon has grown from an ecommerce retailer into tablets (the Fire lineup), smart home devices (Alexa), cloud computing storage (AWS), music streaming (Amazon Music), video streaming (Amazon Video), photo storage (Amazon Photos), book streaming service (Audible), tv hosting (Firestick), and through other business units and acquisitions. The multitude of these content and data engines is that Amazon products have become integral to our productivity and lifestyles. The aggregate effect gives the retailer tremendous power in manipulating whole industries.

Imagine for a moment if Google had its own ecommerce marketplace and fulfillment centers, and they sold similar products to yours.

Pretty intimidating isn’t it? A Statista report found that Google accounted for 84% of all searches online in January 2020.

There’s no way any company could compete with their search engine dominance. Just ask Microsoft’s heavily-marketed Bing with only a 6.25% share…

Now consider that Amazon has double the amount of users starting their product searches on their site instead of Google.

There are likely a multitude of factors that have put Amazon so far in front of Google (and everyone else) with why consumers start their product searches there. But the most dominant factor is Prime membership loyalty.

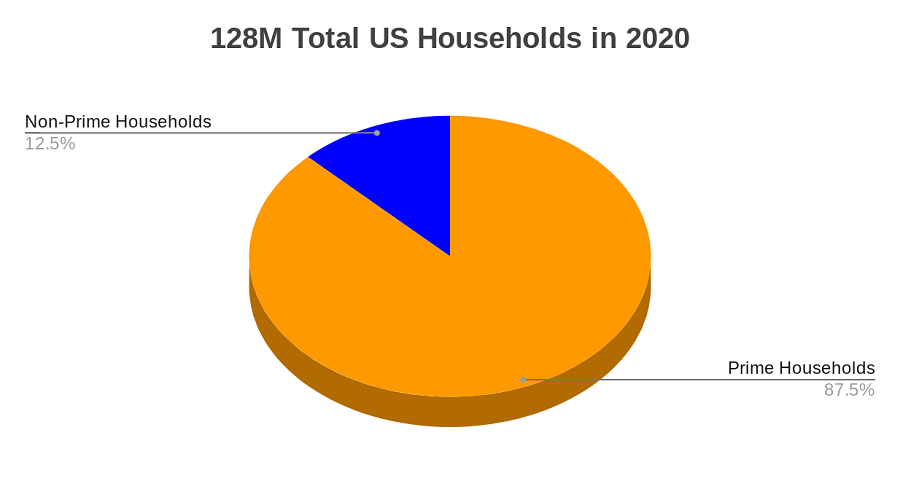

And how many Americans have a Prime membership today? A whopping 112 million, which represents 87.5% of all 128 million U.S. households.

In other words, roughly nine out of 10 U.S. households start their product searches on Amazon three out of four times.

That averages to roughly two-thirds of all product searches starting on Amazon every day.

So if Google is a far second to Amazon on product searches and the lines between offline and online sales are blurring, how can anyone else compete? It’s time as an industry to band together to form a more compelling platform to contractors.

More on that later.

About Luke Powers

Luke Powers is the founder and CEO of Gearflow.com, an AEM member company and marketplace built for construction equipment professionals to find the parts and equipment they need from vetted suppliers. For more information, visit www.gearflow.com.

Luke Powers is the founder and CEO of Gearflow.com, an AEM member company and marketplace built for construction equipment professionals to find the parts and equipment they need from vetted suppliers. For more information, visit www.gearflow.com.

About the Association of Equipment Manufacturers (AEM)

AEM is the North America-based international trade group representing off-road equipment manufacturers and suppliers with more than 1,000 companies and more than 200 product lines in the agriculture and construction-related industry sectors worldwide. The equipment manufacturing industry in the United States supports 2.8 million jobs and contributes roughly $288 billion to the economy every year.

Constructionshows

Constructionshows